Visible Cloaks: Synthesis and Systems

According to the dictionary, synthesis is the combining of constituent elements of separate material or abstract entities into a single or unified entity. Apart from the familiar technical sense of creating complex sounds from simple waveforms, synthesis also describes what we do when we take our influences and inspirations and make them the foundation of our individual creative voices.

Of course, influences and inspiration can come from anywhere, and as with any flow of information, filters are needed to fish out what is special or potentially meaningful. Increasingly, algorithms are doing a lot of the filtering for us (Spotify playlists, Youtube recommendations, etc.) – and while the machines are getting better and better at predicting what might interest us based on our past behaviour, nothing beats being personally led into a musical world one didn’t even know existed and immediately falling in love with it.

For a good many listeners, two mixtapes intriguingly named “Fairlights, Mallets and Bamboo" (Vol.1 and Vol.2), were exactly this kind of highly specific guided tour; in this case, into the surprisng connections between 1980s Japanese electronic pop, ambient and so-called “world music”.

The mixes, originally posted on the Root Strata label blog in 2010, featured music by artists little known outside of Japan (along with luminaries such as Ryuichi Sakamoto, Haruomi Hosono, and Yellow Magic Orchestra) and were subtitled “An investigation into fourth-world undercurrents in Japanese ambient and pop music, 1980-1986”. With their artful (and even prescient) juxtaposition of digital textures and traditional timbres, the tracks featured on the "Fairlights" mixes resonated strongly with listeners and music makers curious to learn more about the unexplored byways of electronic music's global history.

The compiler of these mixes was one Spencer Doran, who together with Ryan Carlile makes up Visible Cloaks. The pair recently released their second album, “Reassemblage”, on the New York-based RVNG Intl. label and, not surprisingly, the three-dimensional sound design, artful arrangements and contemplative mood of the album reveals the influence of the Japanese artists featured on the aforementioned “Fairlights” mixes. But as our interview with Spencer below reveals, what informs Visible Cloaks’ music-making ranges further and wider than any particular historical confluence of styles and sounds. Crucially, it is the duo’s systematic way of connecting music to ideas from other disciplines that makes their highly original synthesis possible.

Where are you two from and how long has Visible Cloaks been a going concern?

I grew up in Northern California (where Ryan and I first met) and have lived on the west coast of the US for my whole life. My background is in philosophy and Ryan’s is anthropology, we both have undergrad degrees but veered away from academia. Visible Cloaks started out as my own solo project, as simply “Cloaks”, which has gone through a string of transformations and lens shifts since. We’ve used the current iteration of the name for a few years now.

With Visible Cloaks one immediately hears how very specific your sound world is – to the extent that it’s very difficult to pinpoint any direct influences. Is there any particular musical lineage you see yourselves as being part of?

I’ve always been very drawn to the sense of compositional space utilized by composers associated with INA-GRM and have learned many lessons listening to those records over the years. Also, our work is very much in the tradition of American composers like Paul Lansky, Carl Stone and Paul DeMarinis, in the way that they work with digital tools in a deconstructive fashion, like using technology to tease out the underlying musical elements in linguistics. There’s also more conceptual kinds of thinkers that have a different kind of influence – Pauline Oliveros, R. Murray Schafer, Brian Eno & Haruomi Hosono’s use of cybernetic systems…also [Geinō Yamashirogumi founder and Akira soundtrack composer] Tsutomu Ōhashi on many levels.

The music and locational sound design of Hiroshi Yoshimura, Satoshi Ashikawa and Yoshio Ojima is another thread that weaves heavily into our work, which itself has this specific form of avant garde serenity flowing through it that can be traced back to folks like Erik Satie. Ojima designed a whole caché of ambient music to be played within the interior of Fumohiko Maki's incredible Spiral Building, which was an arts/culture center funded by the Wacoal lingerie company (and an apt symbol of the corporate patronage that was deeply intertwined into the cultural landscape during Japan's 80s asset bubble), so there's a metabolist connection there.

Hiroshi Yoshimura worked extensively doing locational sound design intertwined with public architecture, things like interface sounds for the Kobe subway system, sound logos for the Hayama modern art museum, entrance music at the plaza of the Yokohama soccer stadium, etc. There's this dialog with physical space in their work which springs from the whole concept of music as "environment", as this thing that exists within (and is inseparable from) the natural sound world. It greatly affected the way I think about acoustics conceptually - working with recorded sound as this sort of interim between the imagined world one creates within a DAW (or whatever you're composing in) and the real physical space it actually inhabits when played back.

Ashikawa envisioned environmental music not being something that exists separate from external reality, but as something that overlaps with a given space and shifts the space's meaning. I think both are possible, or at least - as I said in the other section - our work aims for a kind of duality.

What does your production workflow look like and when do you decide that a piece is finished?

We have no set process, and are always moving between different workflows to keep things fresh (think This Heat’s “All possible processes, all channels open” philosophy). I also have always preferred working in a collage of approaches, in an attempt to get results that are more multi-hued in their meaning and thus present the listener with something more complex to explore and unpack in the listening experience. There’s usually a fairly long route to a piece being “finished”, and there’s often a few different arrangements of a given piece that we end up choosing from.

Are there any creative strategies (oblique or otherwise) you employ to aid you in your productions?

There’s lots of different strategies in the mix. For example one tool we use often is taking an audio sample and turning it into MIDI information (using Melodyne or Live’s Audio to MIDI function) and then using only the MIDI information in the final piece so you are only hearing the melodic imprint of the sample instead of the sample itself. We also use a lot of MIDI randomization as a form of aleatoric composition – Walter Zimmermann has this concept he calls “non- centered-tonality” where his intention is to free his compositions from the determinism of a pre-written structure, allowing him to experience the music freshly – in the same way the audience does with a new piece. He was using matrix systems and mathematics to achieve this (inspired by methods used in traditional Chinese music) but our intention is similar. This process has to be “frozen” when doing a mixdown for an album, but remains very alive in live performances and installation work that we’ve done.

Do the two of you have distinct roles?

Our roles are not too specific, though my strengths are more in the composing, editing and arrangement side and Ryan is more involved in the improvisation and use of electronics/hardware, plus controlling the virtual wind instruments with an Electronic Wind Instrument (he’s trained as a saxophonist). A fair amount of the abstract elements in our sound design are recordings of Ryan improvising on electronics that I cut up and process further during the editing stages, and there is a lot of layering and manipulation of time events within any given piece.

There seems to be a very precisely considered palette of voices and textures in your music. What instruments and sound generators are you using and what kind of processing are you applying to them?

It’s a very mixed bag. Without giving too much away I’ll say that we use a blend of hardware and software. There’s a lot of physically modeled VST instruments, which work with samples of actual instruments and have this fascinating sort of hyper-real sheen to them. "Valve" makes use of Soniccouture’s Pan Drum and Tingklik (in chromatic mode) running MIDI data translated from Miyako Koda's voice. Ironically, we have a real tingklik in our studio but – and perhaps this underscores a point – what we're doing with it isn't possible with real instruments.

This [physical modeling] technology is so widespread at this point that companies make instrument packs that are marketed to, used and made by “non-western” cultures – like you can go on Youtube and watch insane videos of virtuosic Azerbaijani musicians shredding some mugam but it’s all on software. Using a breath controller headset, the pitch bend knob, etc. It’s an interesting inversion of the relationship that music technology has had with traditional instruments in the past, which is one intertwined with exoticism and cultural signaling as opposed to functionality (take the shakuhachi sample on the Ensoniq Emulator for example, with it’s almost foley-like function). It’s just one of the many ways that the reach of globalization has shifted the relationship between technology and traditional music – globalization is decimating a fair amount of the world’s ancient musical traditions, but it’s also fusing with them with technology in the same way that migration has shaped the evolution of instruments for thousands of years. I think it’s worthwhile to investigate this form of artifice and its implications regarding representation, cultural or otherwise, as it most certainly is the direction we are headed.

The shakuhachi flute preset from the 1984 Emulator II – famously used in “Sledgehammer”

Just to indulge in some speculation for a moment, do you think that our greater familiarity nowadays with traditional sounds (real or virtual) from around the world might lead to more music makers incorporating non-western rhythms, harmonies, tunings, and other ways of composing and organizing sound?

I don't think that my generation is any more tuned into traditional music than generations previous – certainly the more esoteric aspects of human culture are more accessible than ever, but one still needs to have an interest in them to explore them. There most certainly are structures that are hard-coded into us by western popular music – I spent a great deal of my post-college years immersing myself in things like ethnographic field recordings, musique concrète & early pre-classical music in a conscious attempt to un-learn as much of that as possible. But as some folks get more comfortable with venturing outside of our own cultural landscape, institutions like "rock and roll" or even "house music" continue to become increasing un-varied and dogmatic, so I don't think a paradigm shift will ever really be possible.

Back to Visible Cloaks’ music; your productions sound very meticulously arranged at both macro and micro levels. How do you think about and work out the interaction between the details and the ‘big picture’ of a piece?

I suppose you could say it’s very heavily arranged. I’ve always enjoyed the elasticity that organizing sound with software allows, and the ability to zoom between (as you said) macro and micro. I think it’s interesting to create work that can function on multiple listening levels – things that are unobtrusive on the surface (and thus can function in environmental/ambient situations) but have enough attention to detail and complexity that they can be scrutinized by close “deep” listening as well. I’ve always been interested in making music that is atmospheric and yet non-static – which is where a more meticulous approach to arrangement and song structure comes into play.

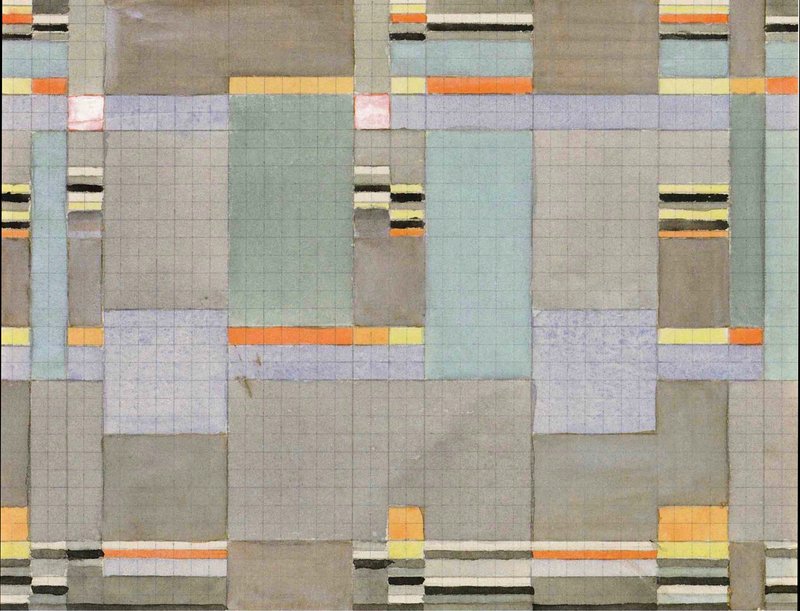

Arrangement as aesthetic structure, the past as it leaks into the future. “Entwurf für Doppelgewebe” (Gunta Stölzl, 1926)

Architecture and interior design have a great impact on the way I think about acoustics and the organization of sound – there’s a shared sense of arranging things within three dimensional space (the stereo field, the frequency spectrum and time) and giving thought to the way in which they are embellished, adorned with details, etc… I guess it’s like some form of spatial synesthesia but it’s a pretty natural extension of thinking of music as a series of systems.

Keep up with Visible Cloaks on Soundcloud and Twitter