Luke Sanger: A Workman’s Tools

There’s no fixed rule for how an artist relates to their tools. For some, one or two critical instruments may define their entire creative identity. For others, like Luke Sanger, the medium is secondary to the end result, and often in electronic music there are many different ways to achieve the same sonic aim.

“I've had the same acoustic guitar that I got off my dad when I was a teenager, and I'd never consider getting rid of that,” says Sanger as we catch up over Zoom, “but I found with electronic gear, for me it's a means to an end. Some bits stick around because I like how they work, but often I get rid of it on a whim and get something else.”

Sanger is a typically omnivorous music lover, with a winding history through underground electronic music that touches on off-kilter techno as Luke’s Anger and playful electro as Duke Slammer, but in more recent times he’s been exploring more experimental and gently paced electronics under his own name and as Natsukashii. The latter project manifested on a low-key cassette release Driving East, and featured experiments carried out solely using an open-source FM soft synth called Dexed. That particular investigative tract yielded a specific sound, but his other non-dancefloor work has progressed in tandem across a plethora of studio approaches.

Tracks leftover from Driving East fed into a pool of music which Sanger sent through to Balmat, a new label founded by electronic music critic Philip Sherburne and Albert Salinas of Lapsus Records. The end result of this connection is Sangers’ latest album Languid Gongue, which hangs together surprisingly naturally for a project drawn from a variety of practices.

“The initial conversation with Balmat was around a load of bits that I had leftover from other albums,” explains Sanger, “so there was distinctly psychedelic electro-acoustic stuff, some Monome, some synth, some violin, bits of guitar and all sorts of things I'd been experimenting with, and one or two FM synth tracks, which I did with the Dexed. Having Philip, who listens to a lot of music as a journalist, picking through these sounds and making choices I would never have thought of got me quite excited to make some new sounds to go in there.”

An Album Takes Shape

Languid Gongue is a well-rounded album experience marked out by varying shades of beatless electronics. It’s largely pitched as an ambient project, but there are enough pronounced rhythms and forthright melodic elements to question that tag. Rather, it’s a warm and approachable kind of experimental electronica which takes cues from West Coast synth aberrations and deals in wobbly pitches, loping time signatures and a full spectrum of detail. If there’s one overarching feel to the record, it would be one of ecosystems and organic matter. They might move and manifest in different ways, but each track has the quality of a biome housing interdependent species, forming patterns through their existence which are as beautiful as they are unpredictable.

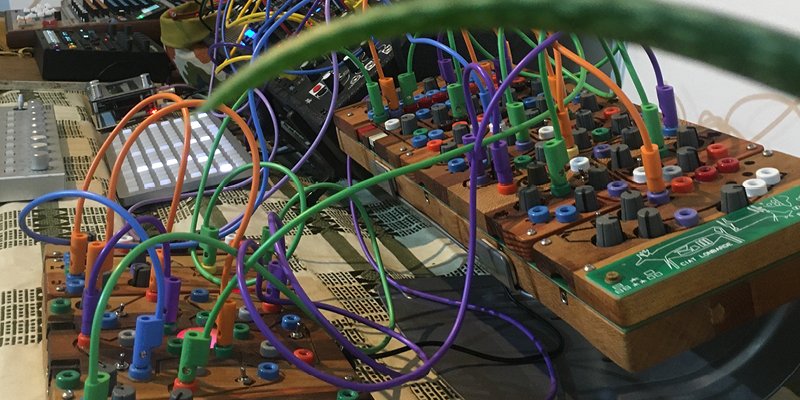

Of the many tools he reached for on the album, Sanger’s use of Ciat-Lonbarde devices was a major factor in giving the album a natural, off-grid energy. After doing a full modular system-swap with a friend during lockdown, Sanger explored these notoriously oblique instruments and left a few of his offhand experiments in the playlist he first offered to Balmat.

Two of Luke Sanger’s Ciat-Lonbarde devices

“Philip picked out some of the really odd microtonal experiments I've been doing with the Ciat-Lonbarde stuff,” says Sanger. “Those pieces were very much led by the equipment, because there's no quantization to pitch. Even the clocks in them are weird and wonky. Once I accepted that they were playing me as much as I was playing them, I started getting on with them a bit better, and they put me down some weird paths of composition I just wouldn't have considered otherwise.

“What I quite liked was the label’s suggestion these experiments could be peppered throughout the more produced tunes, like the old Raymond Scott albums where you'd have advert music, and then some theme tune to a programme, and then an experiment on a really primitive sequencer or something.”

You can hear the results of Sanger’s exploration into Ciat-Lonbarde on the tracks ‘Coco n Plums’, ‘Basic Lurgy’ and ‘Fruity Textures’. They are indeed the odd diversions that break up the more harmonically grounded parts of the album, where even temperament slips away and we head into the intriguing world of microtonal scales. Sanger admits, although he has knowledge of alternate tuning systems, his own approach here was simply tuning the Ciat-Lonbarde gear by ear and looking for frequencies which created rhythmic, psycho-acoustic effects when holding down more than one note.

Past Visions of the Future

As well as serving as a narrative device within the album, these short pieces also go the furthest in sculpting strange, alien worlds. Perhaps these impressions are a hangover from mid-20th Century sci-fi, which was usually soundtracked by early synthesizer experimentation and often featured a similarly flexible approach to tuning. But there are other world builders who fashion distinctive environments with their music, especially in the world of modular synthesis. Sanger namechecks Aphasic Forest by Lee Evans, released last year on Human Pitch, as a good example of someone using modular synths to sculpt beautiful landscapes. Evans’ label mate Tristan Arp also works in similar ways, while the likes of Kaitlin Aurelia Smith and Emily A. Sprague are frequently heralded for their skill in creating musical organisms through their preferred systems.

A track from Lee Evans’ Aphasic Forest – inspiration for Luke Sanger

Zooming in to Microsound

Following Balmat’s initial response to the range of tracks he shared with them, Sanger then set about writing more material to shape out the whole album. When it came to working with his own modular synth set up, which is primarily based around the Make Noise Shared System, he’d pull out every cable and start a new patch every time, seeing where his explorations would take him.

“There are certain traps I fall into out of habit like having the reverb and delay at the end of the chain,” Sanger admits. “The times when I break that habit can be interesting, but I can get where I want to be really quickly with [my system]. But with this natural organism approach, rather than thinking about the linear composition, I try and think of macro and micro. Whatever I’m patching into, I like to layer the main driving element to the tune with much more microscopic versions, something like looking at the whole world from space and then zooming right down to the ants. It’s an idea directly influenced from Curtis Roads' Microsound book.”

As well as using his Eurorack modular system, one of Sanger’s other current sources of technical intrigue is the Monome system. With its roots in a grid-based sequencer-controller, Monome have expanded to develop other devices centered around norns, a highly flexible system which runs scripts to enact just about any musical task you can think of. With a vibrant community of users creating freely available scripts, it’s fast becoming its own microcosm of music technology. The track ‘Mycellium Networks’ on Languid Gongue started out as a norns-based experiment using a looper Sanger wrote the script for himself, free for any norns users to access here.

“There are lots of very kind people in the norns community that have done a lot of the hard work and made some really cool scripts,” Sanger explains. “What I do as a sort of programmer is tinker about with them and change bits that have already been done. They're particularly good for DSP processing, loopers, and things like that. I was using a couple of loopers a lot on ‘Mycellium Networks’, jamming into them with a blues progression using an FM synth, then using these really weird loopers to loop it back, play over the top and dump it into Live. Then the puzzle begins, ‘how do you turn that into something a bit more cohesive?’ Sometimes it doesn't work, sometimes it does.”

Live as Canvas

With all the outboard experiments that fed into Languid Gongue, Sanger would run his results into Live for final processing. In some instances it was no more than a landing point for a stereo capture from his mixer, or at other times he was piecing together individual elements to create the whole picture. In the case of ‘Yoake’, which forms something of a centerpiece to the album, the entire track was made in Live using the aforementioned Dexed plug-in. Dexed is open-source, free for anyone to download, and it’s faithfully modeled on the iconic Yamaha DX7, a notoriously tricky synth to program. ‘Yoake’ was made in the wake of Sanger’s Natsukashii album, responding to the early 80s Japanese ambient music by artists like Hiroshi Yoshimura which often featured the clean, crisp sound of the DX7.

“I find tracks like ‘Yoake’ quite straightforward to plan because they tend to be pentatonic FM synthesis,” says Sanger. “I can hear the DX7 so straight away I can think about how I'm going to set up the project, and then have a few instances of Dexed – one for bass, one for chords and one for melody. In terms of compositional approach it's probably the least unusual on the album.”

While it might not be as challenging as the laborious menu diving on an original DX7, Dexed is still a challenging environment to enter for the uninitiated. Sanger’s grasp of FM synthesis is strong enough to build a good electric piano patch from scratch, but he’s happier to save painstaking hours and source the ideal kalimba and other patches from the internet and tweak them to his needs. Fortunately, Dexed also works with the original DX7 patches, making those classic sounds easily available within the enclosure of a freely available soft-synth.

Passing Sines

Beyond ‘Yoake’, one of the starkest examples of Sanger’s in-the-box work can be found on a recently released library music album for Apache Music called Passing Sines. The album’s description bills it as ‘ambient analogue modular synth explorations’, but in fact many of the tracks were made mainly using Live 11’s Inspired By Nature Max for Live devices. The new Instruments and Effects have closed the gap between Sanger’s work with hardware and software, encouraging a more experimental approach within the DAW environment as he might similarly experiment with a synth.

“I think the approach with Live and with outboard for me is very similar now,” Sanger muses. “I use everything in a really experimental way, approaching the plugins like I would approach modules on a modular synth. As someone using Live since version one, before it had MIDI, it felt to me like they were going back to those times when it was a bit more of an experimental tool than just a full on DAW.

“The majority of tracks on Passing Sines started life using the new Live 11 tools as starting points. ‘Eleven Ways’ is the most obvious example, using the new drone machine as the backing, then the Bouncy Notes plugin to trigger the Vector FM device, with some of the new granular effects and delay on top. I didn’t use the timeline or BPM for any of the sequencing, just automating things in and out as it felt right.”

Weaving a Consistent Voice

It speaks to Sanger’s creative intentions that he manages to impart a consistent musical identity throughout these myriad approaches – Passing Sines feels akin to his work on Languid Gongue, even if the album on Balmat was completed well before Live 11 was released. In particular, there’s a certain quality in the synth voices he works with, where the pitch flutters and the notes fall in pearlescent drops. It’s unmistakably rooted in FM synthesis, but across Languid Gongue it turns out there was one common source for many of the synth voices.

“Ah yes, that’s one of the secrets of the album,” Sanger laughs. “The [Elektron] Digitone was one of the main synth voices that pops up on a lot of the tracks, but even with those I was playing them into the norns, looping and re-sequencing them. But that wavery sound is just a patch I dial up. It's really easy to make an FM patch from scratch on the Digitone. They make it so easy compared to the Dexed, the engineer must have been a musician.”

Tunes, Not Tools

When so many approaches feed into the process, a consistent synth voice can easily be the glue that holds a whole project together. In the case of Languid Gongue, which started out as a scattered selection of offcuts from different projects, the Digitone voice becomes a familiar figure traversing the curious landscapes Sanger creates. Folding the space between a DAW, plugins, systems, voices, effects and mixing desks, everything in the studio becomes modular, able to patch in and out of each other without falling victim to ill-conceived ideas around what should or shouldn’t be used. As the lines blur between the different tools at our disposal and what their function is, the idea of one approach being ‘authentic’ starts to fade from view – something Sanger wouldn’t seem to miss.

“There seems to be a trend for electronic artists defining themselves by their tools, calling oneself a ‘modular synth artist’ or announcing your album specifically by the tools used to create it,” he points out. “It creates a preconception for the listener before they’ve even heard the music. The great thing about the sheer vastness of inter-connective audio tools available is it's easily possible to choose your own combination of DAWs, plugins, hardware, modular, pickups, contact mics, acoustic instruments, microphones, to make something unique.”

Behind the interfaces and systems though, there are more fundamental musical concerns which Sanger believes should come in front of what tools you use.

“The more you can understand how things work compositionally, it'll always guide that into something that's more listenable,” he argues in a tone that hints at his background in music education. “I think there's always a trap that people can fall into where they say, ‘Oh, I didn't like computers because I had too many plugins, so I got into modular or DAW-less,’ but they're actually not going to make anything better that way. That kind of stuff dwarfs a lot of the good content out on the internet, because people like showing off what they've got, and that's fine, but it does make it a bit harder to find the good tunes.”

Text and interview by Oli Warwick

Keep up with Luke Sanger through his website, Instagram and Soundcloud.